Glushkov made substantial personnel changes at Aeroflot that included, among other measures, the firing of a number of secret service agents that were operating abroad under the auspices of Aeroflot’s foreign affiliates

The death of Nikolai Glushkov on March 12 that followed the recent poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia, further fueled the tensions in Great Britain over the suspicion that Kremlin is behind yet another assassination.

It seems quite reasonable to believe that Russian intelligence services cast a long cloud of influence over Glushkov’s life and death. Indeed, the course of his life changed forever in 1997 when he and Boris Berezovsky became a target of investigation of the Department of Justice of the Russian Federation in connection with Aeroflot, the Russian airline where Glushkov served as a Vice President in 1996-1997.

The impetus for the Aeroflot investigation was the fact that Glushkov, in an attempt to turn an otherwise loss-making state enterprise into a profitable private company, made substantial personnel changes at Aeroflot that included, among other measures, the firing of a number of secret service agents (from both FSB (Russia’s Federal Security Services) and GRU (Russia’s Military Intelligence Directorate)) that were operating abroad under the auspices of Aeroflot’s foreign affiliates. These same individuals essentially controlled financial operations of Aeroflot outside of Russia and thus the company was perpetually generating losses. In an interview to a Russian newspaper Kommersant, Glushkov described the situation as follows:

“In reality, Aeroflot’s assets and profits were already transferred without any input from the company’s management to separate enterprises that served the interests of certain employees. Approximately 450 foreign bank accounts with varying degrees of legitimacy were receiving company’s profits on behalf of more than a 100 different enterprises. Russia’s Central Bank’s authorization was received for each of these accounts. Current profits of Aeroflot that were handled in this manner amounted to approximately $80 million to $220 million. At the same time, all of such “representatives” of the company were the agents of the various branches of Russia’s secret service, which precluded any degree of accountability.

From the beginning of my employment with Aeroflot, a problem arose with the employees who were also working for the Russian intelligence. Out of 14,000 employees, there were at least 3,000 of these individuals, including the Head of Human Resources and the Head of Security, both of whom were FSB officials or officers. We inconvenienced them quite a bit by consolidating all of the finances that were previously controlled by them into a single accounting center. The first call that I received at the beginning of the summer of 1996 was from General Alexander Korzhakov, who headed up the Security Service for the President of Russian Federation. He was livid, stomping his feet and yelling at me that he would destroy me if I were to continue impinging the rights of the FSB operatives. Mikhail Barsukov, who was the Head of the Russia’s FSB, took similar tone with me. It was really the Secret Service organization that initiated the events that ensued in 1998-1999.”

Glushkov was found dead in London on March 12, 2018. Police suspects that he had been strangled to death. Photo: ЕРА

Glushkov was found dead in London on March 12, 2018. Police suspects that he had been strangled to death. Photo: ЕРАIndeed, as soon as 1997, Aeroflot’s management was changed and Glushkov was forced to leave. It was around the same time that he became a subject of a criminal investigation concerning embezzlement of Aeroflot’s funds.

The interview with Glushkov was published on November 23, 2000. Two weeks later, on December 7, 2000, he was arrested in connection with the investigation that commenced back in 1997. This was really a revenge of the Secret Service for the firing of their employees who were working abroad under the auspices of Aeroflot, and for the closing of the Aeroflot foreign bank accounts, which were in substance under the complete dominion and control of FSB and GRU.

Since December 7, 2000, Glushkov was incarcerated in the pre-trial detention center Lefortovo while the investigation continued. Under the Russian Federation’s law, he could be detained practically indefinitely. Around February 20, 2001, he was transferred from the pre-trial detention center to the Department of Hematology at the hospital so that he could receive the medical treatment that was necessary for his declining health while remaining in custody. All of a sudden, Department of Justice announced on April 13, 2001, that Glushkov made an attempt to escape.

“The Department of Justice announced today that Nikolai Glushkov, one of the main suspects in the so-called Aeroflot case, tried to escape from the hospital where he was receiving treatment while in custody. The Department of Justice suspects that Glushkov’s guards organized the escape, which was masterminded by Boris Berezovsky and Badri Patarkatzishvili, the current CEO of TV6, the television company…… Nikolai Glushkov and his two accomplices were stopped at the hospital gates when they were attempting to get into a car….. The prosecutors have reasons to believe that if successful, Glushkov’s escape would have ended up with him being taken outside of Russia.”

Berezovsky was vague in his response to this announcement: “No one has ever accused me of being ineffective. Of course if I decided to kidnap Glushkov, although this scenario seems incredible, I would have succeeded. There is no doubt about that.” Patarkatzishvili, too, denied playing any part in Glushkov’s failed escape. In the meanwhile, Glushkov was transferred back to the pre-trial detention center Lefortovo and the term of his incarceration was extended. The Department of Justice now commenced a real criminal case against him in connection with his attempt to escape. In other words, only after Glushkov’s failed “escape” did the Department of Justice obtain any real case against Glushkov himself, as well as against Berezovsky and Patarkatzishvili as the organizers of his botched escape.

Glushkov, too, was allowed to relocate to London in 2006. He continued to assert that Lugovoi was a provocateur who worked for the FSB

To be fair, one should note that Badri and Boris were actually planning to move Glushkov abroad with Lugovoi’s assistance. Glushkov, however, had always considered Lugovoi a provocator who was acting at the direction of his FSB superiors. But Berezovsky and Patarkatzishvili started to believe in Lugovoi’s innocence after his “arrest” and were now attributing the failure of Glushkov’s escape to inexplicable circumstances.

Lugovoi’s arrest charade had generally worked and only Glushkov, who continued to be detained, was the one who continued suspecting Lugovoi of double play. Everyone was released in March of 2004. Lugovoi received a 14-month prison sentence, with the time served at the pre-trial detention center counting towards that period. Glushkov, in turn, received a 3 year-and-3-month prison sentence, and was also released based on the fact that he already served that time at the pre-trial detention center.

Glushkov, however, was not allowed to leave Russia even though he applied for an exit visa, but Lugovoi was not only allowed to operate a private security business (which requires a special license issued by both the law enforcement agencies and intelligence agencies), but was also issued a foreign travel passport, including his trips to London, during which he managed to become a confidant of Berezovsky, Patarkatzishvili and Litvinenko based on his status as a “victim of Putin’s regime.”

As it were, Glushkov, too, was allowed to relocate to London in 2006. He continued to assert that Lugovoi was a provocateur who worked for the FSB. However, no one believed Glushkov. Later, formal evidence emerged supporting the claim that Glushkov’s “attempted escape” and Lugovoi’s “arrest” were staged by the FSB: indeed, at the time of his supposed “arrest”, in June 2001, Lugovoi was an FSB major. In 2007, after Litvinenko’s poisoning, he was already a Colonel. It seems that he received these promotions for his successful handling of Glushkov and Litvinenko, respectively.

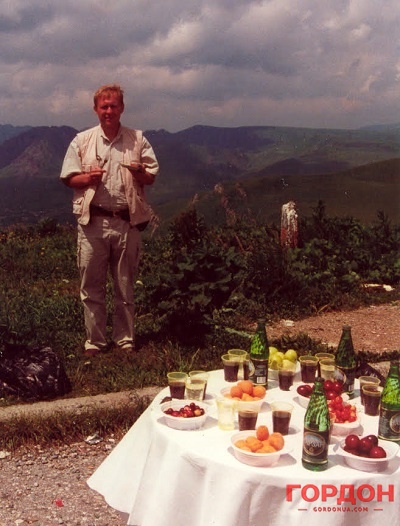

Lugovoy in 1999 during his visit to Dombay in Karachay-Cherkess Republic. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

Lugovoy in 1999 during his visit to Dombay in Karachay-Cherkess Republic. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

During that period, I used to see Lugovoi in London frequently. Since my stay in Moscow in 1998-2000, we established a decent relationship. He made an impression of an FSB operative who was somewhat of an intellectual and a gentleman – a rarity among his peers. I appreciated his pleasant manner and friendliness. However, since the day that Litvinenko gave his (in)famous press-conference in November 1998, Lugovoi maintained that Litvinenko was a traitor who would end badly. At the time, I considered this view as a nod to the reality of the situation: Berezovsky was a Russian State employee at the time, and Lugovoi was serving in the FSB and could not really view Livinenko’s actions any differently.

In response to my questions as to what he was doing in London, Lugovoi invariably answered: “I have some common business ventures with Badri; we are in the process of some negotiations here.” Badri was Boris’s business partner, and all of Boris’s business assets were registered in Badri’s name. The legend perpetrated by Lugovoi was that Badri entrusted him with several million dollars to conduct business in Russia. This information was difficult to verify and it would have been useless to ask Badri.

A botched “escape” of Glushkov and “incarceration” of Lugovoi in June of 2001 were the first few steps of a multi-step scheme, which culminated on November 1, 2006, with the poisoning of Litvinenko that was planned as a perfect murder with indeterminable poison. It seems that there were at least two other cases where substances similar to polonium might have been used: the poisoning of Yuri Shchekochihin in Ryazan’ on June 16, 2003 (he died on July 3, 2003) and the poisoning of Roman Tzepov in St. Petersburg on September 11, 2004 (he died on September 24, 2011). In Tzepov’s case, the official conclusion was that the death ensued from radioactive poisoning. Both Schekochihin and Tzepov took 13 days to die. For Litvinenko, it took 22 days (given that he received better care in Great Britain, and did not smoke or drink alcohol).

A few days before Litvinenko’s death, on November 20, 2006, mass media published a few quotes from Oleg Gordievsky, a legendary KGB officer who worked for British Intelligence for a number of years and whose escape from the USSR was organized by the British just as he was about to be discovered and arrested. Gordievsky mentioned that Litvinenko was poisoned by the two FSB operatives, with whom he met on the day that he became ill. I called Gordievsky.

– Oleg, with whom did Litvinenko meet that day?

– I do not know their last names. But I do know that one of them worked as part of Berezovsky’s security detail.

– I do know the name – I said to Gordievsky and called Berezovsky right away.

– Boris, do you know who poisoned Litvinenko?

Boris seemed ill at ease:

– Do you want me to tell you the last name of that person? – he asked, with irritation in his voice.

– Yes, the last name. Can you tell me?

– Of course not.

– But I can: it’s Lugovoi.

The last name of the second person – Kovtun – was not known to anyone at that time.

Boris was silent for a few seconds and then exclaimed emotionally:

– How can you think of a person so poorly? I have known him for many years. And you know, on that day, he was at my office as well. Why didn’t he poison me while he was at it? Can you answer that question?

– Boris – this is an easy question. He did not receive an order to that effect.

No one sent tea to Berezovsky, but in June 2007, someone sent as a “gift” to him a hired assassin of Chechen descent with a teenager

It so happens that in April 2007, a man contacted me by phone and informed me that there would be an attempt on Berezovsky's life. He described quite a few details of the planned operation, including the name of the purported assasin. That person was supposed to get in touch with Boris when already in the UK, introduce himself as an old acquaitance with whom Boris had some business in the past, make plans to meet, kill Boris during the meeting, not leave afterwards and allow himself to be arrested. For that detailed and seemingly plausible information (at least part of which could be verified if needed), he asked to be paid €10,000-€20,000, promising to return this money the first chance he gets.

Obviously, I informed Boris immediately, composed at his request a memorandum regarding this matter in both Russian and English (with the latter having been sent to the British police) and went on with my life with a sense of fulfilled duty. Boris refused to pay anything for this information. My informant called a couple more times and asked me to talk to Boris again. But Boris was not inclined to pay.

Nevertheless, on June 16, the person named by my informant arrived at the Heathrow Airport. He was recognized by the border partrol and a 24-hour surveillance was set up. He checked into the Hilton Hotel located within a two-minute walk from Berezovsky's office. Because of the hotel's proximity to the office, everyone who visited London to meet with Boris stayed at that hotel.

Lugovoy and Irina Pozhidaemaya, Berezovsky ’s secretary, at Berezovzky’s 55th anniversary on his villa near Nice in January 2001. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

Lugovoy and Irina Pozhidaemaya, Berezovsky ’s secretary, at Berezovzky’s 55th anniversary on his villa near Nice in January 2001. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

On that same day, the British Police informed Berezovsky that a purported assassin arrived in London with a teenager (whose presence was supposed to make the situation look more innocent). Berezovsky was advised to leave UK immediately, and he flew to Israel on his private jet with Police on board on the same day. From Israel, in Police’s presence, he held (and taped) several conversations with the “visitor” who asked for a meeting. Boris pretended that he was in London but too busy to meet right away. After five days, on June 21, the suspect was arrested by Counter-Terrorist Unit of Scotland-Yard and charged with conspiracy to commit murder in the UK. After two days of questioning, on June 23, he was put on the plane and sent back to Moscow without any formal charges having been filed. There was no public outcry in Britain following this chain of events.

In July 2007, the press got wind of the thwarted attempt on Berezovsky’s life. My informant called right away:

– You really would not pay me even now? Everything unfolded just as I described. It is a usual custom to pay for the information that leads to crime prevention.

I promised to speak with Boris again and tried to do that a few times, raising a question about the payment and trying to convince him to pay. Boris promised to think about it but never paid. When the informant called me about the payment for the last time, he listened to my explanation and noted with philosophical sadness:

– Well, it’s really up to you…. You will be receiving no other warnings.

And this was indeed the case. No one warned us about anything anymore.

When I told this story to one of the people who was associated with Russian Secret Service, describing the particular cynicism of the masterminds of the attack who decided to bring an innocent boy to London so as not to raise any suspicion, the person to whom I was telling this story smirked and said:

– You really understood nothing. The boy was supposed to carry out the assassination. These are specially trained kids. He is underage, so under the British Law, he could not have been convicted. No one would have bothered with him and he would have been sent back to Moscow right away.

Now Glushkov himself was found dead - the last witness to Lugovoi’s “activities” in Russia and abroad

In April 2008, there was an attempt to poison Oleg Gordievsky in the UK. Oleg barely made it. A legendary British spy who was awarded with the Order of the British Empire by the Queen, was demanding that MI-6 investigate the matter, but he was told to keep quiet and not make any noise. I remember how he called me, confused, and was asking for advice as to what to do. I advised him to make the story public.

In 2012, the businessman by the name of Alexander Perepelichny was found poisoned in London. Again, the British decided not to make too much fuss about this. Then in 2013, Berezovsky was found hanged. Glushkov asserted on numerous occasions that Berezovsky was killed. However, no one thought it worthwhile to conduct any serious investigation. Now Glushkov himself was found dead - the last witness to Lugovoi’s “activities” in Russia and abroad.

I am not sure whether there is any connection between the poisoning of Skripal and the death of Glushkov. But if it were possible to poison Skripal who was exchanged for Anna Chapman, then, probably, it was possible to eliminate Glushkov who was allowed to go to London some time ago. Just as was the case with Litvinenko, Skripal and his daughter were poisoned with a substance that was previously tested in Russia: on August 1, 1995, that same poison was used in Moscow to kill a famous politician and businessman Ivan Kivilidi. His mobile phone was smeared with poison. On August 1, Kivilidi was brought to Central Hospital in Moscow in a coma. On August 4, he died. On August 2, his secretary Zara Ismailova was taken to the hospital because she was having seizures. She has been answering calls using Kivilidi’s mobile phone all day. She died on August 3.

The bodies of Kivilidi and Ismailova were studied in the morgues of the Central Hospital and the Burdenko Military Hospital for ten days. The diagnosis at death was indicated as acute heart failure. However, one of the pathologists, Iosif Laskavy, refused to perform autopsy of Ismailova even then, suspecting poisoning and stating in her medical records: “There are signs of poisoning with an unknown substance."

Lugovoy at Berezovzky’s 60th anniversary near London in January 2006. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

Lugovoy at Berezovzky’s 60th anniversary near London in January 2006. Photo from personal archive of Yuri Felshtinsky

The origins of the poison were established soon: it was produced at the state military chemical facility in city of Shihany in the Saratov Region. This information made it to the media through Dmitry Ayatzkov, who was the Governor of the Saratov Region at that time. In 1997, the MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs) of Russia announced that, according to the forensic examination, the substance with which both Kivilidi and his secretary were poisoned, was a military-grade nerve agent which was a phosphorus-containing poison produced at the classified facility in Shihany. The elements of the agent were discovered in Sweden in 1957. They are transparent, imperceptible to the naked eye and are easily diffusible. They make their way into the human body through skin or through the respiratory system. Death ensues in a few hours, with its cause impossible to determine without a very complicated analysis.

Stanislav Nesterov, the head of the Shihany Administration, was perplexed by the announcement made by the MVD of Russia: “This nerve agent is super-modern and its formula is strictly classified. Neither I nor local FSB is aware of any illegal sales of this substance. If something like this took place, it would have been a scandal of international proportions. Imagine, here in Shihany, anyone can buy poison used in secret service operations from the State Institute of Organic Synthesis.”

On January 17, 2001, the Department of Justice of the Russian Federation announced that they, too, performed an examination to determine the cause of Kivilidi’s death. The Chief Forensic Examiner of the Department of Justice, Alexander Kaledin, stated that the substance used to poison Kivilidi is “a unique formula, the name of which is strictly classified.”

However, it turned out to be difficult for the name of the poison to be kept secret for too long. In a 2002 US movie (i.e., “The Sum of All Fears”, based on the eponymous novel by a famous US writer Thomas Clancy), the Russian military used the nerve gas Novichok in Chechnya. Thus, this "secret" was revealed after the Kivilidi assassination.

On October 9, 2006, Moscow’s Chief Prosecutor, Yuri Syomin, made an official statement that Kivilidi “was poisoned with a substance so unique that it cannot be compared to anything else”, while “we do know how it was produced.” The Head of the Laboratory of the Institute of Evolutionary Morphology and Ecology of Animals, Yefim Brodsky, gave an interview on this subject to one of the Moscow newspapers:

“Using special equipment we were able to quickly determine the formula of this poison. It is a nerve gas similar to sarin.

– Do we know where these types of substances can be produced?

– I am aware of several laboratories.

– Can you name them?

– No.

– Who do you think could have poisoned the mobile phone?

– The person who knows how to handle this substance.

– What if the killer, who purchased it, received detailed instructions?

– It would not be possible to train an outside person to carry out such an operation without the risk of being poisoned while setting up the poison for the target.”

Thus, it appears that the poison used on Skripal, is sufficiently known because of the Kivilidi case. One of the theories is that poison was smeared on the door handle of Skripal’s house.

It is noteworthy that the Litvinenko poisoning was carried out by FSB, while Skripal was probably poisoned by GRU. Setting scores with the children of the “traitors” is an approach that comports with the “traditions” of that organization. A Polish Colonel named Richard Kuklinski who worked for the U.S. intelligence during the period of 1972 through 1981, inflicted significant damage on the Soviet Army as a result of his espionage activities. In 1981, when his apprehension in Poland became inevitable, he and his family were moved to the United States. In 1993, his younger son Bogdan went missing during a sea trip. In August of 1994, his older son Waldemar was hit by a Jeep in broad daylight, in the middle of a university campus in Phoenix. The culprits were not found but the Jeep was discovered with no fingerprints. In 2004, Kuklinski died; he was posthumously promoted to the rank of a General of the Polish Army.

During the assassination of the former president of Chechnya Zelimhan Yandarbiyev that was carried out by the GRU officers in Qatar on February 13, 2004, by placing a bomb under his vehicle, his 13-year old son Daud was severely burned. Two of Yandarbiyev’s bodyguards were also killed.

Two GRU officers who were officially listed as non-diplomatic employees of the Russian Embassy in Qatar were detained by the local authorities a few days after the incident. They were convicted of murder and sentenced to a lifetime in prison. The third terrorist – First Secretary, Embassy of Russian Federation, Doha, by the name of Alexander Fetisov, was “saved” by his diplomatic status. He was declared persona non-grata and expelled from Qatar. On December 23, 2004, the GRU officers serving the life sentence were extradited to Russia and greeted at the Vnukovo government airport in Moscow with military honors, with the red carpet rolled out for them all the way to the ramp of the airplane.

According to the law that passed in 2006 in Russia, eliminations of the enemies of the state by the intelligence services have to be carried out in all cases only with the authorization of the president Putin

The audacity of the Russian intelligence services on the British territory was triggered by the inaction on the part of the British authorities who refused to undertake any meaningful investigation even in the cases where all of the evidence pointed to an assassination attempt or to an actual assassination. In the case of Litvinenko, the investigation happened due to the persistence of his widow, Marina Litvinenko. In the case of the poisoning of the Russian businessman Alexander Perepelichny, the investigation took place at the insistence of Bill Browder since Perepelichny served as a witness in one of the court proceedings involving Browder and Russia. In the cases of Gordievsky, Patarkatzishvili and Berezovsky, no meaningful investigations have been conducted. But by refusing to investigate suspicious poisonings and deaths, the British Government only encourages new terrorist acts since the crimes lead to no punishments, and Putin sees it all too well.

As noted, all of the atrocities committed by the Kremlin are met without any appropriate response. If, in November 2006, as a response to the poisoning of Litvinenko, the British Government were to declare top ten Russian billionaires and their families personas non-grata (beginning with Roman Abramovich, especially since he is the first alphabetically anyway), the shackled Lugovoi would have been delivered to London by December 1. As it stands, however, Lugovoi was given a Russian Parliament (Duma) mandate, a post of the deputy in Zhirinovsky’s party, order issued by Putin, multi-million-dollar business and a rank of colonel.

Nowadays it is no longer possible to resolve the crisis by refusing the British visas to a handful of Russian citizens. But if that number were to be increased to 1,000 or 10,000, the resolution may become more plausible. Better still, if all of the Russian party members who were represented in the Russian Parliament and who adopted the law in March-July 2006 that allows Russian intelligence officials to eliminate Russia’s enemies outside of Russian Federation, were declared personas non-grata, then – maybe – the Russian Parliament would think twice before behaving so insolently and provocatively towards Great Britain. If you add to that list the families of the party officials who are also members of the Duma, the husbands would “cry” for help after being “harassed” by their wives and children who would now be deprived of the right to go shopping in the UK.

To be clear, we are talking about tens of thousands of the Russian citizens who would fall under that ban. If you think even broader, such that all NATO countries were to subscribe to the ban, even a person with a sign “GRU defector” would be safe to walk the streets of London. Note that no one would have to be deprived of their money, property, or of their soccer club “Chelsea” (since all these are well-hidden and protected by the British laws and lawyers). One just has to “take away” all of the Great Britain and all of the continental Europe and U.S.

And if anyone who is reading this thinks that Colonel Skripal could be killed without the nod from the superiors, allow me a little quiz: could GRU poison in the UK an officer who was subject of an earlier exchange without vetting this issue with the Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu? Of course not. And could Shoigu, who received his post as the Minister of Defense from Putin solely for his lack of initiative and loyalty, had given an order to kill Skripal without notifying his buddy Putin, especially on the eve of the elections? We all know that the answer to this question is no.

If it turns out that in the case of Glushkov, it was a political, and not a domestic homicide, then his murder, too, could not have been accomplished without coordination with Putin, since after the Litvinenko’s case, the FSB would not have dared to carry out an assassination of another political immigrant from Berezovsky’s circle in London. It is especially true since after Glushkov’s murder, it is completely natural to suspect that Badri Patarkatzishvili and Boris Berezovsky were also killed because Putin had many more reasons to eliminate them than to eliminate Glushkov. Note that according to the law that passed in 2006 in Russia, eliminations of the enemies of the state by the intelligence services have to be carried out in all cases only with the authorization of the president – a post at which Putin remains for yet another six years.

0 Kyiv

0 Kyiv